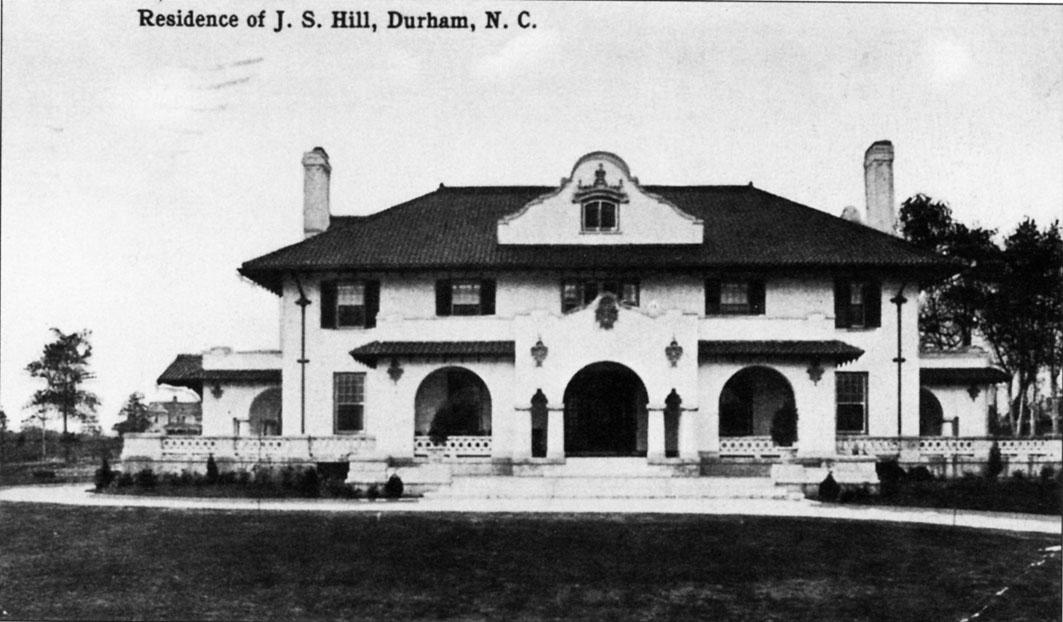

Hill House, 1910s-1920s.

(From "Images of America: Durham" by Stephen Massengill)

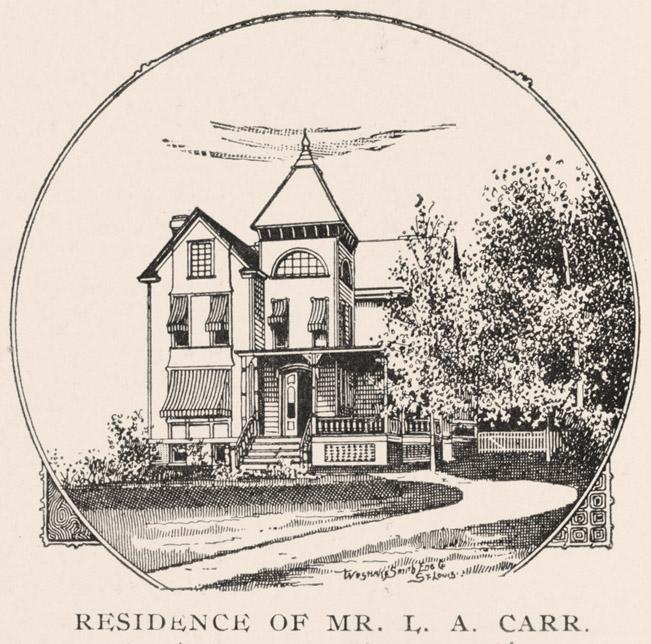

Louis A. Carr, despite the familiar last name, was not directly related to Julian Carr; rather he came to Durham from Baltimore in the late 1880s or early 1890s. He became a partner with Samuel T. Morgan in the Durham Fertilizer Company, and along with Julian Carr and George Watts, he formed the Interstate Telephone and Telegraph company in 1894, about which I've written more here.

Carr married George Watts' sister, and built a house just to the south of Watts' in the newly developing Morehead Hill 'suburb'. Below, Carr's house in 1895.

(Courtesy Duke Archives)

Carr was a member of the Durham City Council in 1895. His name disappears from the secondary records soon thereafter - I presume that he likely died in the late 1890s or early 1900s. However, the location of his house would soon become the residence of another prominent citizen of Durham.

John Sprunt Hill was born in 1869 in Faison, Duplin County. He attended UNC, taught school in North Carolina, and then attended Columbia Law School. After practicing in New York for several years, He married George W. Watts' daughter in 1899, and moved to Durham in 1903.

Hill and his wife initially lived in George Watts' original Morehead Hill house, which he had moved to the east side of South Duke St. to make way for his even grander house, Harwood Hall. In 1903, Hill established the Durham Bank and Trust Co. and the Home Savings Bank.

By 1910, George W. Watts had acquired the home and land of LA Carr (his brother-in-law) and sold or gave this to the Hills. They hired architects Kendall and Taylor of Boston, who had just completed work building the new Watts Hospital (funded by George Watts) to build this Spanish Colonial Revival house. The house was different in style, but similar in mass and grandeur to the other mansions of Morehead Hill, with vegetable gardens, orchards, greenhouses, stables, and other supporting structures (as outlined here) on the southern portion of the land and tennis courts, putting greens, and a rose garden on the same square as the house.

Hill House, 1910s-1920s.

(From "Images of America: Durham" by Stephen Massengill)

Hill became a pivotal figure in the history of Durham - and Chapel Hill, and not only for the rise of his banking interests (which would be housed in his namesake building) into what became Central Carolina Bank. He also founded the Farmers' Exchange and helped establish credit unions in North Carolina; he served in the NC Senate from 1933-1939.

He played a strong philanthropy role at the University of North Carolina, building the Carolina Inn in 1924 and donating it and its grounds to UNC in 1935. He donated significant funds for endowment of the North Carolina Collection at Wilson Library at UNC, and established a chair in the History department. He served on the building committee and as a trustee, donating significant sums for campus expansion.

Hill House, looking northwest, 1924

Back in Durham, he and the Watts and Dukes donated the money to buy the old Stokes homesite on Fayetteville St. for the Lincoln Hospital in 1917. He gave the city the land for Hillside Park. He acquired the golf course at Forest Hills and donated it to the city for a park in 1930. He donated a large tract of land on the East side of town to the city in 1932 for parkland, which the city divided up into a park for African-Americans (East End) and for whites (Long Meadow.) He donated land for a park at Branch Pl and Proctor, no longer extant. He purchased Durham Athletic Park and donated it to the city in 1935, and gave the 149 acre Hillandale golf course to the city in 1939.

Hill House, 1940s (?)

(Courtesy State Archives of North Carolina: PhC68.1.31.2)

When he died in 1961, he donated his house to a foundation created in his wife's name, the Annie Watts Hill Foundation, for the use of non-sectarian, non-political female organizations. The Junior League of Durham of Durham and Orange Counties makes its home here, although it is open to any group meeting the aforementioned criteria.

Looking west, 2007. (G. Kueber)

02.13.14 (G. Kueber)

From Preservation Durham Home Tour 2022 "Then & Now"

This historic mansion is important as much for its association with the family who created and lived in it as it is for its architectural grandeur. Through their commitment to education, civic-mindedness, public improvement, and philanthropy, John Sprunt Hill and his wife Annie Watts Hill made enormous and indelible contributions to Durham and to the State of North Carolina. Fortunately, they had the foresight to preserve their home for posterity and today we can continue to remember and admire both this house and the Hill legacy.

John Sprunt Hill was born on a Duplin County plantation four years after the end of the Civil War - the middle child of eleven. At age twelve, he left school to work at his father’s country store for four years, and later he taught high school for two more. He attended the University of North Carolina and continued there for law school but finished his degree at Columbia University in New York. He became a successful attorney in the city and was active in local and national politics. Hill became a valued counsel to Tammany Hall politicians at a time when the city was rapidly expanding.

While representing a Manhattan finishing school, Hill met and fell in love with fellow North Carolina native Annie Louise Watts. Annie was the only child of wealthy Durham entrepreneur and philanthropist George Washington Watts, a partner of the Dukes in their many enterprises, including the American Tobacco Trust, the Erwin Cotton Mills, the Durham and Southern Railroad, and the Durham Electric Lighting Company, which operated the City’s streetcar network. John and Annie married, and soon after the birth of their first child in 1903, they returned to North Carolina. The couple settled in Annie’s hometown of Durham, renovating her parents’ first Durham home which had been moved across the street to make room for the Watts’ new house, Harwood Hall. An extraordinary Chateauesque Style home, Harwood Hall was located on Lee Street (later Duke Street) in Morehead Hill among the mansions of other affluent Durham families. Unfortunately, that great home was demolished in the 1960s.

With his father-in-law’s backing, John Sprunt Hill grew extremely prosperous with one successful venture after another. In 1904, the two founded the Home Savings Bank (predecessor of CCB and SunTrust) and built the Trust Building at West Main and Market Streets to house it. Hill continued to build Durham’s commercial architectural landscape for the next half century.

The Hills’ family was burgeoning also and the couple began to build their new home on a four-acre parcel south of Harwood Hall that had been owned by Watts’s brother-in-law, L. A. Carr. The Hills hired accomplished Boston architect Bertrand E. Taylor to create the Spanish Colonial Revival Style. Taylor’s firm had recently built the new Watts Hospital in 1909. The hospital was one of many of the family’s gifts to Durham.

Construction of the nearly 11,000 square foot Hill mansion began in 1911. The L-shaped plan positioned the main entry and living areas on the front of the house facing Duke Street, with service and support areas in the rear extension.Traditional in form, the Duke Street façade is perfectly symmetrical, with its covered front entry porch the defining element. The center of the three arched bays is the focal point, flanked by stuccoed columns which form Moorish arches supporting a curvilinear parapet. Above, a large Spanish style frontispiece with a casement window extends up through the red clay tile roof and features elaborate baroque ornamentation of carved scrolls, shells, ribbons, pendants, and urns, - a recurrent theme throughout the house.

Single-bay covered porches extend north and south from the sides of the house, the southern porch with a cantilevered heavy-timbered gable serving as a porte cochere. The two side porches connect to the main entrance internally by a wide T-shaped hall with walls covered in seven-foot-high oak paneling with Lincrusta- style wallpaper embossed to resemble tooled leather above. The intersection of the T, directly opposite the front door, is anchored by an enormous fireplace with a richly detailed surround of marble and carved wood. To the left (south) of the front entry is the well-appointed library with its massive fireplace, built-in bookshelves and polished wainscoting of Honduran mahogany. To the right is the music room with its elaborate Colonial detailing and arched window seats. Across the T-shaped hall is the formal dining room, another massive carved fireplace and mahogany woodwork, Tiffany style chandelier, and sterling silver wall sconces. Beyond the dining room are the remarkable butler’s pantry, the kitchen, which still boasts its original cast iron stove, a breakfast room, and several service rooms.

At the north end of the main hall, the exquisitely detailed staircase leads to a wide landing with a short flight returning to the Lincrusta-covered walls of the second-floor hallway. Five of the six bedrooms on this level have fireplaces and the baths retain their original fixtures. The Hill House master suite includes three closets, a separate dressing room, elevator access, and a private bath with a tub, marble shower and foot bath. A seventh door in the corridor leads to a rear stair connecting the kitchen and service areas with the third floor servants’ quarters and storage areas and the attic above.

The Hills acquired an additional parcel of nearly eight acres extending south to Lakewood Avenue, upon which they developed gardens, orchards of nut and fruit trees, heated glass-roofed conservatories, a carriage house, and various other outbuildings in support of their estate. They raised three children here: Laura Valinda, Frances Faison, and George Watts Hill. Annie died at home in 1940 at age 63, and her husband continued to live at Hill House until his death in 1961, at age 92.

The list of buildings attributed to John Sprunt Hill is remarkable. He and father-in- law G. W. Watts purchased and donated the four-acre Stokes estate on Fayetteville Street and led the private fundraising efforts to build a hospital for African Americans there. He built the three-story commercial structures that still stand at 306 & 308 West Main, the Temple Building next door at West Main & Market, the seventeen-story Hill Building (now 21C Hotel), and finally, in 1957, the modernist steel and glass Home Security Life Building at 505 West Chapel Hill Street.

The Hills acquired and donated to the City of Durham the land for Hillside Park, Forest Hills Park, Long Meadow Park, and Orchard Park. They created Hillandale Golf Course and ultimately gave it in trust to the citizens of Durham. They established the Durham Athletic Park and paid for the baseball stadium to be rebuilt after it was destroyed by fire in 1939. Over six decades, they gave the University of North Carolina more than a million dollars, funding the conversion of the 1905 Carnegie Library to a music hall which now bears their name. They donated the funds to establish the library’s North Carolina Collection, and built and donated the 1924 Carolina Inn, its proceeds designated in perpetual support of the library.

The Hills also left their mark on Durham and North Carolina in other significant ways. J. S. Hill was instrumental in creating a system of rural credit unions in North Carolina, implementing concepts he had studied in Europe. He served on the board of the Durham Public Library, the Durham Board of Aldermen, the North Carolina Highway Commission, and the UNC Building Committee and Board of Trustees. He spent five years in the North Carolina State Senate. Annie Hill was a civic leader in her own right, working most notably with the YMCA/YWCA, the Watts Hospital Auxiliary, and the First Presbyterian Church.

Towards the end of his life, J. S. Hill made arguably his two most significant and lasting gifts. In 1958, he contributed to the $1.5 million seed funding that established the non-profit Research Triangle Institute and begat what is now Research Triangle Park. He also established the Annie Watts Hill Foundation, bequeathing to it the family’s Spanish Colonial mansion to be used as a meeting place for non-sectarian, non-political women’s organizations. Notably, Hill left a sizeable endowment that continues to fund the impeccable upkeep of the house and grounds. That vision and the stewardship of Junior League of Durham and Orange Counties over the ensuing decades are why John and Annie Hill’s home still appears largely as they left it, while Watts’s Harwood Hall, Ben and Sarah Duke’s Four Acres, and all but two other grand homes from Durham’s second great boom are now gone.

In 2018, the Foundation and the Junior League embarked on an ambitious program to address ongoing maintenance issues, update critical systems, and restore and preserve the historic fabric of the century old property. The work was performed by Durham’s Trinity Design Build and their team of artisan subcontractors. Broken roof tiles were replaced, and gutters and downspouts were repaired. Windows were re-glazed and repaired, and seventy-five exterior shutters were restored or remade, and freshly painted. Porch pavers were tuckpointed, and stucco was repaired and cleaned before a total repaint with elastomeric paint. Wood soffits and rafter tails were scraped, sanded, and stained,and stone sills and medallions were cleaned and sealed. Wrought iron railings were restored and repainted. The primary entryways were stripped to bare wood and stained.

Inside, air handlers were replaced, plumbing and electrical systems were repaired and upgraded, and the kitchen was sensitively updated, repainted, and fitted with new appliances. Vinyl floor coverings containing asbestos were removed and replaced with period appropriate tile. Interior plaster walls and ceilings were repaired and repainted throughout the house, and three floors of hardwood flooring were sanded and finished with oil-based polyurethane. Ina space that had been used as an office, a new, accessible bathroom was added. This work carefully preserved the room’s vaulted ceiling and lovely fireplace.

This inspiring project has restored the luster to the Hills’ 110-year old Spanish Colonial mansion and given it the updates needed to continue fulfilling the mission of the foundation that bears Annie Watts Hill’s name. Preservation Durham is grateful to the Foundation and the Junior League for their continued stewardship of this unique historic landmark and for sharing it with us on this spring’s tour.

Add new comment

Log in or register to post comments.